May 1974: This is where I came in.

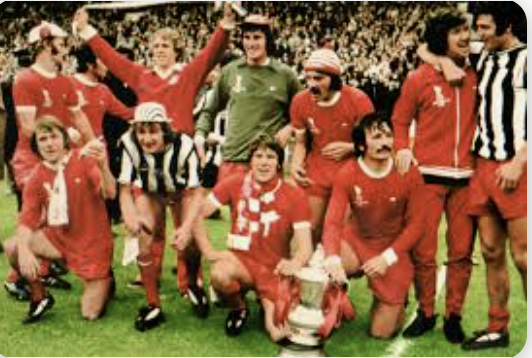

A five-year-old boy sits, not exactly glued to, but rather remotely interested in the events unfolding before him on the family’s black-and-white television. An unusual event is taking place, as a live football match is being shown on the box. The boy’s father is getting himself worked into a lather, and this rubs off on the boy. Intrigued now, he watches the 1974 FA Cup Final unfold into a 3-0 procession of a victory for Liverpool over Newcastle.

Hooked, the lad is now a Liverpool supporter.

The months pass and the boy gets to know the players – not just of Liverpool, but of most First Division teams – by name, and, frankly speaking, becomes just a tad unbearable in his obsession. The next few years see football become an all-consuming passion with far too much time than is healthy being frittered away in the pursuit of meaningless trivia and so-called knowledge, and although this tendency has reduced over the decades, the late middle-aged man that boy became still possesses the ability to spout out by memory that successful Liverpool side.

(Clemence, Smith, Hughes, Thompson, Lindsay: Hall, Cormack, Heighway, Keegan, Toshack, Callaghan, with Lawre as the only substitute.)

Legends all.

Well, ok then, not quite all of them. Some more than others, perhaps.

However, while the majority of these players may well be known to the majority of football fans of a certain age, it is entirely possible that a good few of them may have faded from the nation’s collective memory. Let’s, then, spend a few minutes delving back in time to have a look at some of these (relatively) unsung heroes.

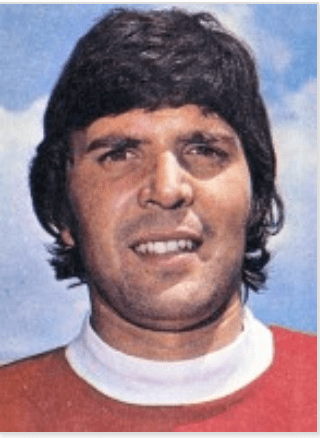

Playing left-back that day, Alec Lindsay thought he had opened the scoring early in the second half when he played a one-two with the legend that is Kevily Keegily on the edge of the Newcastle box before slamming the ball past the hopeless (or hapless?) Iam McFaul in the United goal. Imagine his disconcertion then, when the ‘goal’ was chalked off due to Keegily’s perm straying offside by an approximate distance of 0.0002mm?

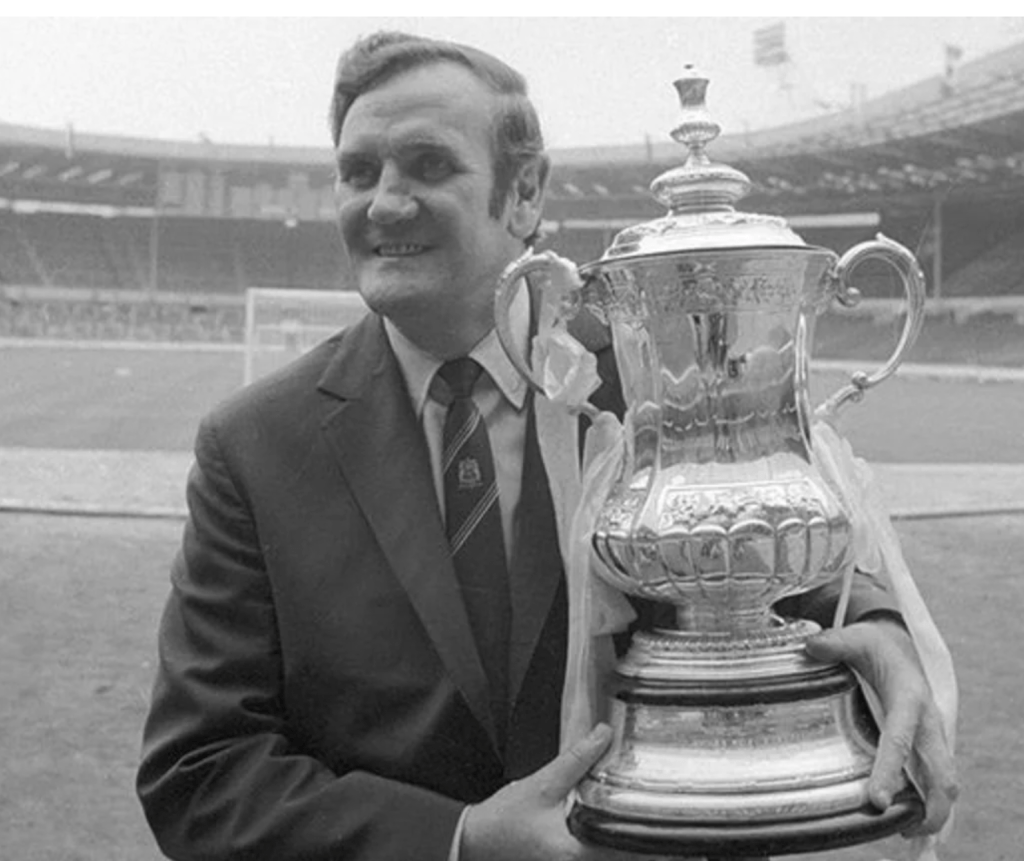

Looking like a roadie for a 1970s glam rock band, Lindsay had a pair of sideboard chops to be proud of. Capped four times by England, all under the caretaker management of Joe Mercer in the summer of 1974, Lindsay originated from Bury, where he played almost 150 matches before being signed by Bill Shankly in 1969. Winning the league title and UEFA Cup in 1973, and the aforementioned 1974 FA Cup, Lindsay stayed at Liverpool until the autumn of 1977, but despite gaining a European Cup winner’s medal from the bench in Rome in 1977, Lindsay’s career at Liverpool began to peter out shortly after that 1974 success. Writing many years later in his autobiography, Bob Paisley, Shankly’s successor, had this to say about Lindsay, “Alec peaked at the end of that successful 1973/74 season but was never the same player again after his life was overtaken by a series of personal problems. Unfortunately, they badly affected his game, and he began to lose heart, which showed in his performances. Sadly, Alec was one of those players who wasted a lot of his talent, and I am sure he would have admitted that himself when he looked back at his career. It all went wrong when he was at the top of his profession.”

After leaving Liverpool, Lindsay spent a season at Stoke City before decamping for a couple of years to the NASL and retiring at the relatively young age of 31.

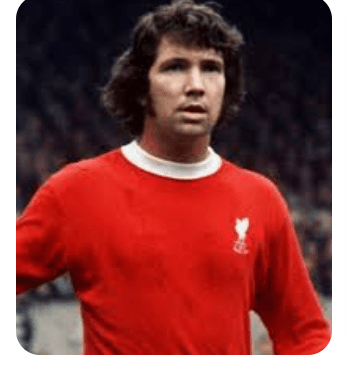

Brian Hall wore the number 8 shirt on that rainy day at Wembley half a century ago now and was many people’s choice for Man of the Match as he industriously broke up what little force Newcastle were offering in midfield, while orchestrating Liverpool’s fluent passing game. Signed from university where he completed a Bachelor of Science degree, Hall’s greatest moment in a Liverpool shirt was arguably at Old Trafford in the spring of 1971 when he scored the winning goal in the 1971 FA Cup semi-final against arch Merseyside rivals, Everton.

Nailing down a place under Bill Shankly, Hall was a stalwart in the side for five seasons before losing his place in the starting line-up to an emerging Jimmy Case halfway through the 1975-76 season. Later admitting he gave up on his Liverpool dream too early, Hall left Liverpool at the end of that season, departing for Plymouth Argyle. Sadly, Hall died in 2015 due to leukaemia.

Lining up alongside Hall in Liverpool’s midfield for their 3-0 demolition of the Magpies was Scotland’s Peter Cormack. Like Hall, Cormack’s Liverpool career would peter out at the halfway point of the 1975-76 season, but before that happened, he would enjoy large swathes of success in the red shirt.

Born in Edinburgh, Cormack started his career north of the border with Hibernian before transferring to Nottingham Forest in 1970. Two years at the City Ground passed before a 1972 transfer to Liverpool, with Bill Shankly telling a bemused Cormack as he signed his contract, ‘he was the final piece in the jigsaw.’ Success followed over the next two seasons as Liverpool captured the league and UEFA Cup double in 1973, and the FA Cup a year later.

A bad injury saw Cormack play his last Liverpool game in December 1975, and following a three-year spell at Bristol City, Cormack returned to Scotland, where he played out the last years of his career back at Hibernian.

After spells in management, Cormack left football altogether in 2002, before sadly passing away due to complications of dementia.

Finally, the substitute that day in May 1974 was long-serving full-back, Chris Lawler. Although only 30 years old, Lawler’s career at Liverpool was already winding down when the red men took on the Geordie counterparts at Wembley. Lawler only made 18 league appearances in 1973-74, and hadn’t featured in the team at all for almost three months before getting the nod from Shankly to take up his place as the only sub on the Liverpool bench.

Liverpudlian by birth, Lawler joined Liverpool straight from school and signed professional forms on his seventeenth birthday. Making his debut in 1963, Lawler nailed down a regular place in the side in the 1964-65 season, appearing in Liverpool’s first-ever FA Cup Final victory in the 2-1 win over Leeds United. The next yen years saw Lawler rack up no less than 549 appearances in all competitions, scoring an amazing 61 goals from the right-back position.

Known as the ‘Silent Knight’ for both the way he would seemingly ghost into goalscoring positions on the pitch and his quietness off it, Lawler was the very epitome of consistency, missing just three league games in an eight-season period between 1965 and 1973. However, a cartilage operation following an injury sustained against QPR in November 1973 spelt the beginning of the end for Lawler at Liverpool, and although he was to stay at the club for another two years, first-team appearances under Shankly’s successor, Bob Paisley, were extremely limited due to the emergence of Phil Neal. Neal, of course, would go on to inherit Lawler’s consistency, meaning that between them the two mean played right-back for Liverpool almost uninterrupted for close on twenty years.

After leaving Liverpool in October 1975, Lawler played for Portsmouth and Stockport County, before spells in Wales, Norway, and the NASL rounded out his career.

Chris Lawler returned to Liverpool for a period as reserve team coach under Paisley and Joe Fagan, before being unceremoniously dismissed by Kenny Dalglish in 1986.